An image of Matariki taken at Te Kura Hapuku, near Kaikōura. Photo: David Hill

Summer was a "mixed bag" this year, according to NIWA.

Wellingtonians, who experienced one of the capital's worst weather starts to the year on record, used more colourful phrases: "A buzz kill", "crap", and "pretty trash".

"Digging back into our records, going back to 1980, this is one of the longer runs of below average daily temperatures that we've had in the summer months," meteorologist Clare O'Connor told RNZ at the time.

But autumn was expected to be warmer and drier for parts of the country, NIWA said.

Even though they were all a bit spring-like to start with, our seasons are changing, scientists say. What does this mean for spring, summer, autumn, and winter as we know and define them?

Defining the seasons

We experience seasons thanks to Earth's tilted axis. Because of the tilt, as Earth orbits the sun, its north and south poles sit at an angle rather than straight up and down.

As NIWA explains on its website: "This tilt means that the sun's rays don't hit Earth equally. The half of the Earth tilted toward the sun receives much more light energy than the half tilted away from the sun."

The half of the Earth tilted toward the sun is experiencing summer, and the half tilted away, winter.

The seasonal effects are different at different latitudes on Earth. The four-season year is typical only in the mid-latitudes.

Places near the equator see little seasonal variation. Meanwhile, in polar regions, winter has periods of continuous darkness and summer brings 24-hour daylight.

Does winter start on 1 June, or on the winter solstice?

We hear a lot about astronomical seasons, which are based on Earth's position relative to the sun. Summer begins on the summer solstice, and winter on the winter solstice.

Earth has a solstice every six months, when one of its poles is closest to the sun. When the Earth's axis is tilted neither towards nor away from the sun, that's called an equinox. It marks the start of astronomical spring and autumn.

But in New Zealand, we tend to use meteorological or calendar seasons: three-month groupings based on the annual temperature cycle.

January is the country's warmest month on average, and July the coldest. Summer is December, January, February. Winter: June, July, August. Fill in the gaps to get the shoulder seasons.

Some Scandinavian countries refer to "thermal seasons", based on mean daily temperatures. The beginning of summer, for example, is defined as when the temperature rises above a certain threshold for several consecutive days.

"There's no right answer," climate scientist Professor James Renwick told RNZ. "It's somewhat arbitrary how these seasonal boundaries are defined."

When it comes to climate forecasting, "seasons aren't used so explicitly", he said. Rather, analysis is done month-by-month.

'It's always spring in New Zealand'

New Zealand's maritime climate is known for being unpredictable. It varies from warm, subtropical in the far north to cool, temperate climates in the far south, with severe alpine conditions in the mountainous areas.

"Four seasons in one day" is a common observation about the country's weather, particularly among visitors from the more settled Northern Hemisphere.

"The fact there's a big continent over the south pole, keeps the weather a bit spring-like all year," Renwick said. "In the Northern Hemisphere, the pole warms up a lot in summer, so westerly winds die off and you tend to have calm, dry weather."

Of course, there's a lot of natural variation in the seasons: "There are all these definitions but in a given year, you'll get something different."

The seasons aren't what they used to be

Despite this natural variation, there's a long-term trend towards longer summers and shorter winters, Renwick added.

Global average temperatures have increased by about 1 degree Celsius in the past century. The average annual temperature in Aotearoa increased by 1.26C between 1909 and 2022. The warmest year was recorded in 2022, with an average temperature of 13.76C.

Warmer temperatures are expected in all parts of the world. The impact will vary by location; some places will experience more wildfires and others more rain.

In New Zealand, data suggests a range of extreme weather events are increasing in frequency and severity. In turn, these affect agriculture, horticulture, fisheries, forestry, and tourism.

GNS principal scientist Dr Nick Cradock-Henry said in the past 15-20 years, any farmer will tell you, there's been a noticeable change in the seasons.

"Multi-generational farmers will tell you they remember walking on frozen puddles as a child, and now, it's rare to get any significant freezing event over the winter."

The shorter winters, fewer frosts, compressed springs, and hotter, drier conditions are impacting plants as well as animals.

"We're really only just beginning to understand the implications of changing management systems to deal with [these things]."

The effects of shifting seasons

"The distinct transition between seasons is becoming increasingly muddled," Cradock-Henry said.

Key development stages of plants and animals are tied to seasonal features such as rainfall, temperature, and day length.

"If you've got lower than usual soil temperatures in February, your ryegrass and clover is behind where it should be. Then you've got hungry animals, which in turn impacts milk production."

The shifting seasons, he continued, "is messing with all of those rules of thumb you've relied on".

Farmers are having to change to accommodate these new conditions. That can mean planting earlier, split calving, and even shifting location.

About 90 percent of Kiwifruit is grown in a single area, in the Bay of Plenty, Cradock-Henry explained. The vines need a period of cool temperatures to produce fruit. Many growers are now moving south, or into the hills, chasing those cooler temperatures.

Others are identifying alternative crops. There are now peanuts in Northland, an increasing number of avocado orchards around the country, and macadamia nuts have been identified as having potential in Hawke's Bay.

The revitalization of Maramataka

Updating our "collective understanding" of seasonal markers is important, Cradock-Henry said.

In recent years, there has been a revitalization of ngā taka o te marama, the repeating cycles of the moon.

Traditionally, Maramataka guided many activities in the lives of iwi such as planting, harvesting, fishing, and hunting. There was variation among tribes depending on where they lived.

This approach can help communities navigate the changing climate through a deeper understanding of the environment, said Te Kahuratai Moko-Painting (Ngāti Manu, Te Popoto, Ngāpuhi), Māori curriculum developer and teaching fellow with the Centre for Pūtaiao at Auckland University.

"That we decide when the seasons change is not implicit in Maramataka," he told RNZ. "Instead, you look for tohu [environmental indicators]."

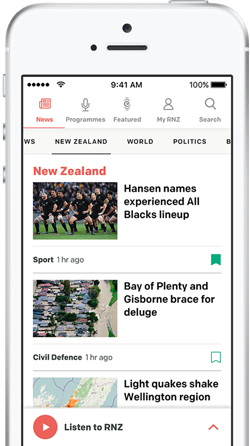

A key tohu is Matariki, the mid-winter rising of the star cluster that signals te Mātahi o te Tau, the Māori New Year. In 2022, Matariki became the country's first indigenous public holiday.

"If the stars are spread out or bunched together, that's a tohu for the coming climate and harvest," Moko-Painting said. "But that's just one tohu of this increasingly unpredictable climate and weather."

Matariki "is just one day", but like many societies, Māori traditionally had a restful period mid-winter, and families spent time together. "It could be a longer period of time," Moko-Painting said of the public holiday.

He stressed the importance of multigenerational knowledge and observation.

"I think of tohu as words in a sentence. You can't know what's being said if you only hear one word. Or even every fourth word."

Ngā taka o te marama has always allowed for seasonal variation: "It was something our tupuna [ancestors] brought to Aotearoa. They adapted this framework to the environment.

"That's one of the strengths of Maramataka, its ability to adapt."

Sign up for Ngā Pitopito Kōrero, a daily newsletter curated by our editors and delivered straight to your inbox every weekday.