Photo: Ruth Kuo

Feral cats are responsible for spreading toxoplasmosis, which can cause "abortion storms" on sheep farms. Methods of control, such as annual culls, have come under fire from animal welfare advocates.

Content warning: This story describes the killing of animals, including an image of a trapped feral cat

It was over beers in a woolshed that the decision was made: Feral cats would be part of the North Canterbury Hunting Competition.

"We just sort of looked around and went, 'Yeah, might as well'," says organiser Matt Bailey.

"Unbeknown to us, it would go off like a powder keg within a matter of days of posting something on social media."

What the farmers thought was a no-brainer decision to add another pest to the competition shocked cat lovers. The backlash was immediate and sponsors of the rural fundraising event came under attack on social media.

But, if anything, the outcry from animal rights advocates made the decision to include feral cats even more popular with farmers and sponsors.

"They poked the bear and it's probably backfired for them because it's gotten people off their asses and out there hunting," says Bailey.

Three years on from the woolshed conversation, the cat category remains popular. This year, contestants entered 326 dead cats for the June weighing-in weekend.

Bailey suspects the real number of feral cats culled was higher. Farmers ran out of freezer space to store the bodies, he says.

"I knew guys catching 10 a week, and they weren't keeping them."

This year, there was no backlash from animal rights advocates, which Bailey reckons is down to increased awareness of the damage feral cats do.

It is one topic where hard-core conservationists and farmers find common ground. Feral cats decimate native wildlife and pose a disease risk to farm animals, and dolphins.

They are found on all types of farms, according to Bailey. On dairy farms feral cats are often spotted near milking sheds or hay sheds. They are also commonly seen near offal holes, or in Bailey's case at lambing time, in paddocks eating afterbirth.

He said he had not heard anyone report an increase in rat numbers after removing cats, adding that if rats do appear, bait stations can be used.

And to critics who argue that trapping, neutering, and releasing feral cats is better than culling them, Bailey has a blunt response: "They're killing our native birds and not shagging them."

How feral cats can spread disease

There is no official estimate of how many feral cats there are in New Zealand. The number of 2.4 million is often cited, but some believe the true number is far higher.

Their number creates a disease risk for every farm in the country, says NZ Veterinary Association sheep and beef branch president and vet Alex Meban.

Toxoplasmosis is carried through cats and spread through their droppings. Tens of thousands of oocysts produced by the virus can be in cat poo, which when accidentally ingested by sheep via grass, hay or water, can be infectious.

Toxoplasmosis can also be passed to humans through contaminated soil, water or unwashed vegetables, and is particularly dangerous during pregnancy or to people with compromised immune systems, but it also affects dolphins and farm animals, such as sheep.

For farmers, there are no outward signs of the disease until lambing time. That is when an "abortion storm" can occur, which is when more than five percent of ewes lose lambs.

"It can be devastating," says Meban. Last season one farmer realised he had lost 30 percent of foetuses during scanning.

"We asked the question about wild cats, the answer was yep, there are lots of wild cats. They hadn't really considered it to be an issue until scanning time."

Lamb losses like this can mean the difference between breaking even or not for a year for a farmer.

There is a vaccine for the disease, and Meban says it only takes one season of heavy lambing loss to convince a farmer to vaccinate flocks. The vaccine costs between $3 and $5 and offers lifelong protection.

If lambs are worth $150 each, he says it does not take much for the vaccine to pay for itself. Vaccination should go hand-in-hand with reducing cat numbers on farms, he says.

Farmer trappers

A Federated Farmers pest survey last year, which had 700 responses, found 37 percent were actively managing feral cats, says the organisation's meat and wool chairperson Richard Dawkins.

The survey showed 2868 cats were culled by farmers over a 12 month period.

Anecdotally, Dawkins says he has heard the number of feral cats is on the rise. He also points to the increased risk of toxoplasmosis and impacts native wildlife.

"I have one farmer report to me that on a braided riverbed, they had a cat take out 90 percent of a fledge of young birds in a colony that was on a river Island," Dawkins says. The cat ate 60 of the chicks of a black fronted tern colony.

Farmers have told him live capture traps are the most effective, but these need to be checked daily, which is a time-consuming exercise for farmers with large blocks.

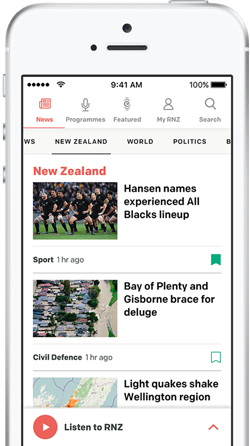

A feral cat caught by a farmer. Photo: Supplied

Cats need to be included in regional council pest management plans, but without extra funding of staffing, "it just becomes words on paper to be honest," Dawkins says.

Increased public education would help, as would support for desexing domestic cats.

The problem increases around holiday periods, which could be caused by people dumping pets, Dawkins says.

"They're a pretty loveable animal, and people may think they're releasing them to run free and have a good life, but they may not understand those implications," he says.

Alternatives to killing

The Animal Justice Party was one of the groups that expressed concern at the inclusion of feral cats in hunting competitions. Committee member Bridget Thompson says the party sees all animals as sentient and objects to the killing of feral cats.

The line between companion cats, strays living close to communities, and feral cats can be tricky for people to discern.

"The problem there is that if people cannot make the distinction, you get self proclaimed eco-warriors in the cities, thinking that if they go out and kill any cat community or companion, they are doing a good thing."

Trapping and desexing is also not the preferred option, Thompson says. Instead, she would like a biological solution.

"We would like to see serious science into interrupting the fertility cycle."

She acknowledges nothing like this exists at present.

Predator fences are also an option until science catches up.

"There's a range of non-violent alternatives to current methods of population control."

Sign up for Ngā Pitopito Kōrero, a daily newsletter curated by our editors and delivered straight to your inbox every weekday.