Raupatu Hetaraka from Ngāti Kahu watching the kaihoe at Waitangi Day 2025. Photo: Layla Bailey-McDowell / RNZ

A leading Māori academic says removing the requirement to teach Aotearoa New Zealand's histories would be a step backwards - and a breach of children's right to understand the country they live in.

Margaret Mutu (Ngāti Kahu, Te Rarawa, Ngāti Whātua), professor of Māori Studies at the University of Auckland, told RNZ teaching local histories gives tamariki a stronger sense of belonging and helps all students understand the places they live.

"Every single school in this country sits within a hapū's rohe. For children to grow up there and not understand who the hapū is, where their marae are, or what the place names mean, that's a huge gap," she said.

"Every child has a right to know whose land they stand on."

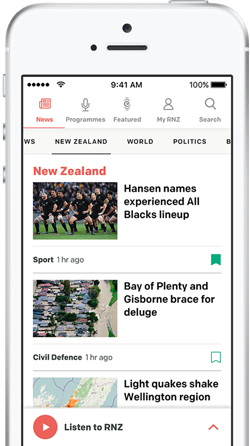

Photo: RNZ / Layla Bailey-McDowell

The proposed changes are part of a growing wave of criticism of the government's approach to Māori language, culture, and Te Tiriti o Waitangi in schools. On Tuesday, the government announced it would remove schools' legal obligation to give effect to Te Tiriti o Waitangi, a move that has alarmed educators and Māori leaders.

In October, Education Minister Erica Stanford released the full draft of the new Years 0-10 curriculum, ahead of a six-month consultation period. It includes plans to fold Aotearoa New Zealand's Histories into the broader social sciences learning area.

The Aotearoa New Zealand's Histories curriculum was introduced in 2023 after years of advocacy from educators and iwi. It made learning about local hapū, colonisation, and Te Tiriti o Waitangi compulsory in all schools, which was a major shift from previous approaches that focused largely on European history.

An Education Review Office (ERO) evaluation found the curriculum was being well received, with Māori and Pacific students among the most engaged. It also found that many teachers felt more connected to their communities.

However, the proposed changes to the curriculum have drawn widespread criticism from educators, principals, and Māori education leaders who say they undo hard-won progress in teaching local histories and Māori perspectives.

Importance of learning local history

Central to the current Aotearoa New Zealand Histories curriculum is teaching local history. It requires ākonga (students) learn about the rohe (region) they live in and the mana whenua of that area - a requirement removed in the new draft curriculum.

But Mutu said learning local history is important for tamariki and staff, to not only understand the country they live in but make sense of global issues.

"Whether you're Māori, Pākehā, or Hainamana (Chinese)... It's important that they can identify themselves within the place they live and relate that more widely when they go elsewhere.

"This kind of knowledge is crucial for teaching values - about relationships between people, how you build them, and how you relate to mana whenua."

Mutu said in her iwi of Ngāti Kahu, the approach is to start by learning about your own place and people, then expand outwards - regionally, nationally, and internationally.

"If you've got that foundation of who you are and where you live, it makes a huge difference to how you approach everything else."

Understanding your own rohe is essential for understanding the wider world, she said.

"If you understand mana whenua, and the realities of having your land and histories taken, you understand what's happening in Gaza or Ukraine.

"What's happening there happened here."

University of Auckland Professor of Māori Studies and linguist Margaret Mutu (Ngāti Kahu, Te Rarawa, Ngāti Whātua). Photo: Supplied / University of Auckland

Mutu said the demand for local resources came directly from teachers, who wanted tools to bring the histories of their communities into the classroom.

In 2017, she published Ngāti Kahu: Portrait of a Sovereign Nation - a book detailing an in-depth history of Ngāti Kahu through the traditions of each of the sixteen hapū of that rohe.

"Teachers were asking for resources to teach about the rohe they were in," Mutu said. "It was there, in the book. But they didn't know how to teach from it."

To fill that gap, Mutu created a 10-week postgraduate course showing educators how to use Ngāti Kahu's histories in the classroom. The response, she said, was "stunning".

"The first course was funded for 20 people - I had 50 enrol. The second had 70, and around 100 observers."

The course gave teachers confidence to weave He Whakaputanga and Te Tiriti o Waitangi into lessons in a way that connected with their ākonga, she said.

"Over half the students in many of our schools are Ngāti Kahu, and teachers now understand how to relate to those tamariki.

"Principals came back and said it's made a huge difference to how they teach."

This approach could easily be replicated across Aotearoa, Mutu said, if the Ministry supported hapū and iwi to develop local resources and lead courses for teachers.

"This kind of teaching enables them to connect to every child in their classroom."

Photo: RNZ / Samuel Rillstone

Associate Minister of Education and ACT Party leader David Seymour celebrated the draft curriculum as a way to "restore balance" to the teaching of history in schools.

He described the current Aotearoa New Zealand Histories curriculum as "highly political" and said it drove a "simplistic victims-and-villains narrative."

"The Marxist 'big ideas' such as 'Māori history is the foundational and continuous history of Aotearoa New Zealand.' and 'The course of Aotearoa New Zealand's histories has been shaped by the use of power' are GONE," Seymour posted to social media.

"In their place is a new and balanced History Curriculum. In line with the ACT coalition commitment to 'Restore balance to the Aotearoa New Zealand's Histories curriculum.'"

However, Mutu believes Seymour's comments reveal a fundamental misunderstanding of place, belonging, and tikanga.

"It makes me sad, because it means David is not familiar with his own background or doesn't understand the underpinnings of his own hapū.

"Those sorts of comments are totally inappropriate. A Marxist analysis doesn't belong in te ao Māori. We don't operate like that, we operate on tikanga."

He Whakaputanga o Te Rangatiratanga o Nu Tireni Photo: RNZ / MARK PAPALII

Mutu said if people truly understood Aotearoa's history, race relations would look very different.

"If people knew the truth, we'd have a much kinder country. But they don't, and they accept racist narratives that blame Māori."

Mutu hoped future generations are not denied knowledge of their place and history.

"Every person here has a right to understand the country they live in. That knowledge comes from each hapū's rohe, not from the government."

She said its "very sad" that most people in Aotearoa don't understand "its true history".

"That's a human rights violation.

"Please stop depriving future generations of the knowledge of whose rohe they live in, who they are, and why this country is the way it is.

"Build a better place for everyone by helping us understand each other."

Sign up for Ngā Pitopito Kōrero, a daily newsletter curated by our editors and delivered straight to your inbox every weekday.