Dr Karen Middlemiss sending off a satellite tagged green sea turtle on Rangiputa Beach Photo: pricilla_northe

Late last year an unprecedented number of green sea turtles, or honu, washed up on New Zealand's coastline.

Many were nursed back to health and released back into the wild - and some were returned carrying special hardware that could help change the way we care for these ocean taonga.

Bella Jansen and Dr Karen Middlemiss carrying a satellite-tagged green sea turtle back into the Rangaunu Harbour Photo: RNZ/Liz Garton

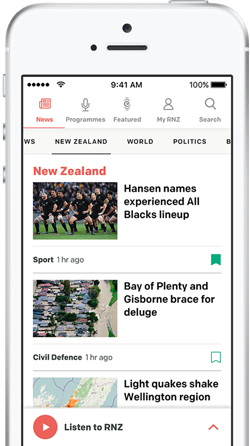

Follow Our Changing World on Apple, Spotify, iHeartRadio or wherever you listen to your podcasts

Where do the turtles go?

Dr Karen Middlemiss, marine senior science advisor for the Department of Conservation, is leading the study, which involves tagging some of the turtles that are discovered sick on our beaches, nursed back to health and then released back into the wild.

"The data that you get from [the satellite tag] will help answer so many questions and really help us better inform conservation decisions for the species," says Karen.

Satellite tagging, step one: Sand and clean the carapace then measure the fibreglass cloth. Photo: RNZ/Liz Garton

The focus of the study is how green sea turtles, which researchers think are semi-resident in New Zealand for part of the year, are using our coastal areas.

"We know that they are resident here because the local communities see them all year round. But we don't know if they're seeing the same turtles or whether some of them are perhaps heading off and it is new ones that they are seeing," she says.

Satellite tagging, step two: Attach the tag with putty, and secure it with more fibreglass cloth and epoxy. Photo: RNZ/Liz Garton

Karen plans to tag 20 green sea turtles over three years.

The tags, which cost roughly $8500 dollars each, will not only track where the turtles go, but also how deep the turtle swims and the temperature of the water where they are spending their time.

Satellite tagging, step three: Coat the satellite tag with anti-foul paint. Photo: RNZ/Liz Garton

Turtle tags

The tags themselves look a bit like a child's walkie talkie, with the aerial coming out the back instead of the top. An area the size of a side plate is cleared and all of it is painted bright blue with anti-foul paint.

"The anti-foul stops epibionts, barnacles, and algae growing on top of the tag," says Karen. "If [the tag's sensors] get covered with anything they won't transmit to the satellite, so we're trying to prevent that from happening."

While the tags appear quite large, everything about them is designed to have the smallest impact, while still helping collect much needed information about the turtles, says Karen.

"We position the tag at the front of the animal so that when they pop up to breathe with their head out of the water, the front of the comes out as well. Then the tag's exposed so the satellites going over will pick it up."

A satellite-tagged green sea turtle ready for release back into Rangaunu Harbour Photo: RNZ/Liz Garton

Sick turtle 'blip'

Finding out how to best look after the endangered green sea turtle could be more important than ever right now.

When turtles are found on the beach, they are likely sick and should be reported to the Department of Conservation. From there they are usually raced to Auckland Zoo for emergency treatment.

Dr James Chatterton, manager of veterinary services at the zoo, said the annual average for the past 11 years has been about nine, but in 2024 there were 22, and 13 of them washed up in just two months - between October and December.

"So, we don't know if this is a blip or if this is the start of more things to come," he says.

Celine Campana, a veterinary nurse at Auckland Zoo who has a lot of experience working with turtles, says that once a turtle develops an illness and then comes into our cooler water, the situation snowballs.

"That's a classic reptile thing," she says. "They're called ectotherms, so they receive their temperatures from externally, they can't generate it themselves. So, when their temperature drops below the optimal performance temperature, everything slowly grinds to a halt."

Turtle rehab

James says the turtles they usually see are in "really poor body condition".

"Lots of parasites, lots of barnacles and other things on the outside of the shell, many have got pneumonia, some have also eaten a fishing hook or been run over by boats or fractured their flipper or other kinds of traumatic injuries," he says.

But the 2024 cluster, although dehydrated, seemed healthier than your average sick turtle.

"They were in good body condition with no barnacles. Instead of taking several weeks to start eating, they took two days or sometimes two hours. It's a real mystery to why they ended up on the beach," he says.

The turtle rehabilitation and tagging takes place at SEA LIFE Kelly Tarlton's Aquarium. Photo: RNZ/Liz Garton

Once stabilised by the care of the zoo staff, the turtles were sent to SEA LIFE Kelly Tarlton's to recuperate further.

"It's really special to be able to get to know a creature like that and to work with them and see them on such an incredible journey from where they've come from," says Kim Evans, displays manager at SEA LIFE Kelly Tarlton's.

She says that caring for the turtles is "pretty intensive" at first, giving injections, antibiotics, tube feeding, getting some pain relief and medication into their system.

And once they start becoming trouble, it's a good sign they are ready to be returned to the sea.

"They become very feisty. If we do have to take them out to weigh them, it's a mission," she says. "As annoying as it is, it's great to see and the relief to be able to release them, it's so exciting.

"But what's really exciting about this time is we actually get to see beyond that release," says Kim.

There's a lot we don't know about green sea turtles. Photo: 123RF

What we do know about green sea turtles

Green sea turtles can be found all over the world.

They hatch and head out to sea and what follows is often described as "the lost years" because it is hard to track the tiny animals in the big wide ocean.

Once they are big enough, they head closer to shore to forage. This is when they appear in New Zealand waters - we seem to have a semi-resident population of sub-adult green sea turtles near the top of the North Island.

While there's no way to tell the exact age of a sea turtle, Celine says their size gives us a good indication of maturity.

"We are getting green sea turtles slightly smaller than dinner plates size and then upwards up to more sort of car tyre size," says Celine.

"And you can probably say that those animals are five- to seven-years old and then probably the higher ends, possibly in their late teens."

Only one in a thousand green sea turtles survive to adulthood and all seven sub-categories of green sea turtle are endangered, with climate change being a huge potential risk.

"The temperature of the sand when a sea turtle is incubating in its egg will directly determine the sex," explains Celine.

"So, there's a what's called a pivotal temperature, and above that temperature you'll get females and below that temperature you'll get males. Unfortunately, all of our beaches are warming up, the sand temperatures are going up and up and without intervention there are many beaches around the world where about 98% of the hatchlings are going to be female.

"So that is going to cause a massive crash in the fairly near future if we don't have enough boys around," she says.

Green sea turtles aren't the only turtle species that show up in Aotearoa but they are the ones we have the best success in rehabilitating and releasing back into the wild.

James says they can get about two-thirds of the sick green sea turtles they see back on their feet, which is a really good success rate.

Other turtle species are not so lucky.

"Olive ridleys that come in, we have zero survival rate and hawksbill turtles that come in, I think we've had two out of 17 survive to release," he says.

There is still a lot we don't know about why the turtles are getting sick and coming up on our beaches, but tagging them is hopefully the first step to filling in the blanks.

A hawksbill turtle, one of the not-so-lucky ones. Photo: Supplied

Sign up to the Our Changing World monthly newsletter for episode backstories, science analysis and more.