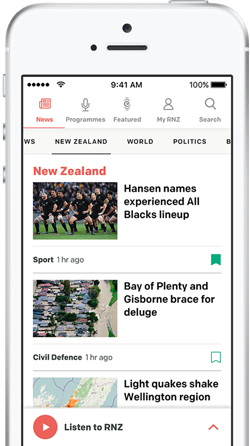

A bedroom inside the secure unit at Te Puna Wai o Tuhinapo youth residence facility in Rolleston. Photo: Mana Mokopuna / Supplied

Young people are being held in seclusion for days on end in youth justice facilities, sparking concerns the units are being used for the wrong reasons.

Secure care units at Oranga Tamariki's five youth justice facilities are meant to be used as an "intensive response" for a young person when they were at risk of harming themselves or others.

The facilities house young people aged up to 18, with the majority being between 14 and 17.

The use of secure care was guided by "internal policies and procedures", Oranga Tamariki (OT) said. But when a young person was held beyond 72 hours, the agency had to apply to the Youth Court for continued detention.

Data released to RNZ by OT under the Official Information Act (OIA), has shown between August 18, 2024 and August 18, 2025 there were 254 instances where a young person was held in secure care for more than three consecutive days.

Out of the five facilities, Te Puna Wai o Tuhinapo in Christchurch had the highest number of instances at 87 with Auckland's Korowai Manaaki next at 75.

The only facility which had zero instances was Auckland's Whakatakapokai which usually housed younger rangatahi. OT said admissions at the facility were paused for part of 2024.

OT said Korowai Manaaki was the largest facility and housed a higher proportion of older rangatahi, including 18-year-olds.

Korowai Manaaki in South Auckland could provide care for up to 42 rangatahi at a time. (File photo) Photo: Peter de Graaf/RNZ

The Human Rights Commission had previously called for agencies to reduce, if not eliminate, the use of seclusion.

In a 2020 report, it found the seclusion of young people was harmful to their health and wellbeing and could further traumatise them and damage their development and healing.

"Secure Care rooms are inappropriate for housing children and young people, and their use should stop," the report said.

A monitoring report of Korowai Manaaki in November 2024, by Mana Mokopuna (Children and Young People's Commission), noted secure care was used frequently and there was little evidence grounds were being met to justify young people being admitted to the unit.

It said one young person at the time of the visit had spent over a week in the unit.

A secure room in a youth justice facility. Photo: DR SHARON SHALEV/ SUPPLIED

One child had been assaulted in every unit they'd been in and they were put into secure care as staff couldn't keep them safe, according to the report.

It said the child regularly asked when they could leave secure care and staff were unable to provide a timeline.

'High level' of extended use

Arran Jones, the chief executive of Arotutuki Tamariki, which monitored OT's compliance, said RNZ's OIA showed there was a "high level" of extended use of secure care.

"It comes as a surprise [to me], it shouldn't be that way when you consider the legal grounds for why secure care is there.

"Seeing kids in there for longer than three days is more than just a circuit break to manage behaviour. Longer than three days is a concern."

Children's Commissioner Dr Claire Achmad said secure care was overused and unfortunately she wasn't surprised by the data.

Children's Commissioner Dr Claire Achmad said secure care was overused. (File photo) Photo: RNZ / Cole Eastham-Farrelly

"We have a team who monitors these places where children are deprived of their liberty and something they look at is the use of secure care."

Jones described secure care rooms as being "small and bare", with a raised platform and a mattress.

"Some have a toilet. That's the environment you're putting young people into.

"Placing them in a room that's devoid of anything therapeutic... think about your own kids spending days in a room."

Achmad had been in secure care rooms and described them as "incredibly basic".

"They are not comfortable bedrooms," she said, "and often no education is offered to them [young people], while in there, so they have very little to do."

The toilet in a secure care room at Te Puna Wai o Tuhinapo, in Christchurch. Photo: Mana Mokopuna / Supplied

When speaking to youth who had been in the units for considerable lengths of time, Achmad said she had been told it was "boring and incredibly lonely".

Young people being held in secure care usually had previous care and protection concerns, Jones said.

"These are kids who have had an absence of love, care and protection. They've likely had access to alcohol and drug use. What you need is highly trained, capable staff who can manage their behaviour."

Who is ending up in secure care?

Achmad said there were instances of secure care being misapplied and misused at facilities.

"Our team takes a detailed look at the records and logs. Too often the grounds for secure care are not being appropriately met.

"We've monitored situations where a young person has been assaulted by staff and are being sent to secure care."

The yard at a secure care unit. Photo: DR SHARON SHALEV/ SUPPLIED

Many of the young people had severe mental health needs, Achmad said, which staff weren't adequately trained to support.

"Children are being voluntarily admitted because of feeling unsafe in the open units. I'm really concerned about this because it means they can end up spending weeks in secure care."

Jones said secure care was an "option of last resort" that should only be used to prevent harm to a young person or others in the facility.

"It is being used to manage young people who aren't wanting to go to bed at night as a punishment or for moderating behaviour that isn't appropriate."

A monitoring report by Mana Mokopuna at Te Puna Wai o Tuhinapo last year noted secure care continued to be used for young people experiencing mental distress or who were refusing to return to open units due to safety concerns.

"It continues to be used frequently and often admissions do not meet the required grounds," it said.

Time for change?

Achmad believed OT had been listening to the concerns raised about the overuse of secure care, but said there hadn't been enough focus on changing the approach.

Oranga Tamariki operates the youth justice facilities. (File photo) Photo: RNZ

"I'm hopeful change will happen but a lot of the answer to this problem is having well trained and well equipped staff."

Jones agreed insufficient training for staff was a driver behind why secure care was used so regularly.

"These facilities don't have the staff that have sufficient training and support to de-escalate the group.

"If you did, you wouldn't need to put kids into secure confinement to keep them safe."

Achmad said she wanted to see OT doing everything it could to avoid the use of secure care.

Minister for Children Karen Chhour said improving safety at state care residencies had been a key priority for her and there had been improved and greater training for staff.

"Training initiatives include frontline leadership training being rolled out across secure residences to ensure teams have the support and specialist knowledge needed to reduce harm.

"They also include better induction programmes for staff and have also been introduced in our youth justice residences, which has a strong focus on safety, including proactive behaviour management."

Chhour said she announced a reduction of harm in state care residencies on Wednesday, with a 14 percent reduction in 12 months.

Legislation clarifying the appropriate lengths of secure care had passed through Parliament earlier this week, Chhour said, and would be signed into law.

Secure care usage reviewed daily - OT

Acting chief executive of OT Andrew Bridgman said staff worked hard to avoid scenarios where secure care was needed, but it was an option provided within legislation to support staff and young people.

Andrew Bridgman, acting chief executive of Oranga Tamariki. (File photo) Photo: Reece Baker/RNZ

Bridgman said young people in secure care still had access to educational activities including group activities.

"Staff support the young person to enable them to safely reintegrate.

"Each residence reviews any secure care usage daily and a child or young person cannot remain in secure care longer than three consecutive days, or 72 hours, without approval by a Judge."

Residences were "dynamic environments", Bridgman said, and the number of young people being placed into secure care and the length of their stay could fluctuate.

"Working with young people who may have high or complex needs can be challenging. Our staff receive training in de-escalation and are guided by a comprehensive Code of Conduct, alongside robust policies and operating procedures that set out clear expectations."

OT worked closely with health providers to ensure young people's clinical needs were met, Bridgman said.

Sign up for Ngā Pitopito Kōrero, a daily newsletter curated by our editors and delivered straight to your inbox every weekday.