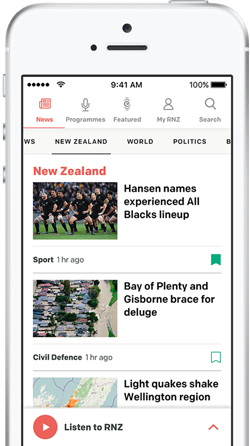

New population data has confirmed that New Zealand will need to rely more on migration to offset an ageing population in the coming decades. Photo: RNZ

More affordable and suitable housing is likely to be a better incentive to get people to have babies than "baby bonuses", economists say.

New population data has confirmed that New Zealand will need to rely more on migration to offset an ageing population in the coming decades.

Stats NZ said on Tuesday that the estimated population of New Zealand was 5.3 million as at 30 June. The median age of women was 39 and men 37.4. In the year, the population grew by 0.7 percent.

The total fertility rate was 1.57 births per woman, marginally up from 1.55 a year earlier. The rate has been below the replacement rate of 2.1 since 2013.

Treasury earlier warned that could cause problems as the cost of an ageing population would be covered by a smaller number of working taxpayers.

In the 1970s, there were about seven people aged 15 to 64 for everyone aged 65 and over. Today there are four and in 50 years there will be about two.

Infometrics lead demographer Nick Brunsdon said it was a situation that had been "in the mail" since the 1960s.

"If the average level of migration is 30,000 a year over the next from now to eternity our population is still likely to start declining in probably the 2050s.

"Migration is the only thing that can save us but it won't entirely save us over the long term.

"We've already become much more reliant on migration than we used to be but we're going to become even more reliant on migration and even more prone to those wild swings that we get in migration."

He said with most households needing two earners, having children was more challenging.

"That's probably where the action is in terms of making it easier for people to leave and then re-enter the workforce - helping with that is much more effective than any kind of big cash payment, I think it would need to be quite a large cash payment to move the dial.

"Other countries have tried throwing money around as a sort of Hail Mary on that front. But the flip side is it's cheaper to get migrants."

The US has been reported to be looking at offering US$5000 "baby bonuses". South Korea was paying 2 million won. China offers 3600 yuan.

But Brunsdon said that was unlikely to be the solution.

"I don't think anyone's going to change their plans for $5000," Brunsdon said.

"We can look and see other countries, there are plenty through Europe that are well below 1.5, China's at about 1.3 children per woman and no one's managed to really avert that in a substantial way."

He said it was a question of managing the impact. "Net migration is really, really weak. Down below 20,000 and we have a net loss of population in the 20 to 34-year-old age group. More young Kiwis are deciding to leave than come here so the challenge is going to get more acute in the coming years because if you're losing the 20 to 34-year-olds they're not going to be here having kids."

Westpac senior economist Michael Gordon said it would take some time before the population tipped into decline.

He said there were "push and pull" factors for the falling birth rate. "We have seen birth rates dropping worldwide, it's not just in rich countries, either.

"As countries get richer on average, they tend to have fewer children. That's something we see everywhere. But there is also an element of push vectors ... there is a reasonable amount of evidence that unaffordability of housing affects this as well.

"It means that people form families later in life. It means they are having fewer children ... the short answer is to do things that improve the lives of everyone in the country and then population trends will change as a side effect of it."

That could mean cheaper housing and an increased variety of options to meet different stages of life, he said.

"More generally just making kind of housing development more family friendly - access to transport and things like that."

That might not only help family size but also encourage people to stay in the country, Gordon said.

"The thing is any kind of population policy will ultimately be thwarted by the fact that people can choose to leave.

"If we do things to make it more attractive for people to stay. Then, as a byproduct to that, you will get more natural population growth. I mean, another way of putting it is there's no point paying people to have more children if half of them leave the country when they reach adulthood anyway."

Sign up for Ngā Pitopito Kōrero, a daily newsletter curated by our editors and delivered straight to your inbox every weekday.