Fossils are the words and strata (layers of sedimentary rock or soil) are the pages of "Earth's diary", says palaeontologist James Crampton. He's joining local iwi Ngai Tuhoe on a hunt for evidence of dinosaur fossils in Te Urewera.

James Crampton hunting dinosaurs in a tributary of the Mohaka River, Hawkes Bay. The truck tube was slowly deflating and became increasingly difficult to ride! Photo credit Julian Thomson, GNS Science

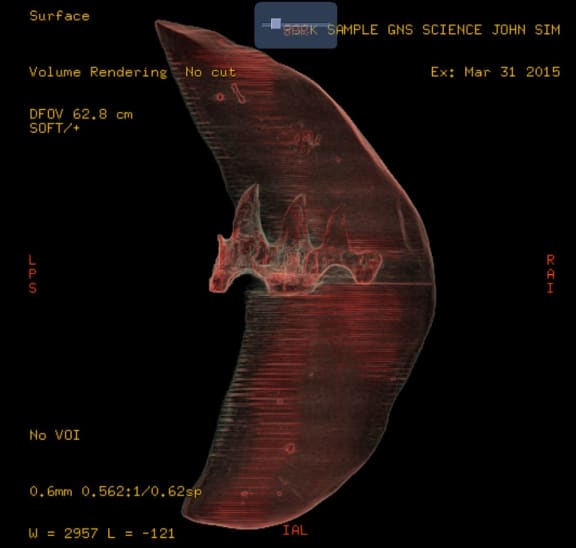

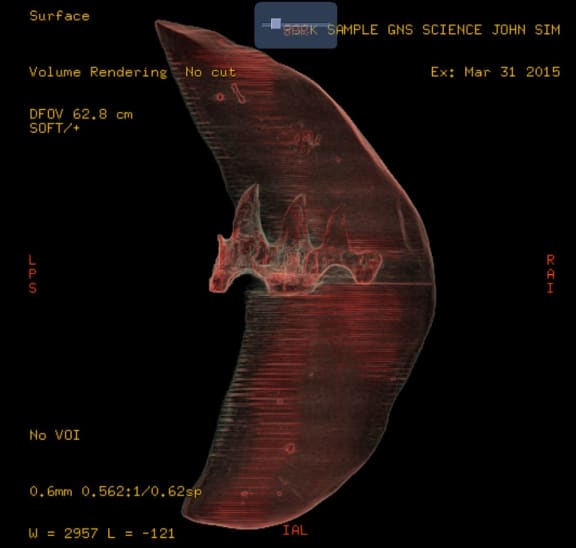

Large block of rock containing mosasaur teeth, collected from the ranges of inland Hawkes Bay. The fossil is about 70-80 million years old. The rock has been scanned in a medical CT scanner and the teeth have been reproduced using a 3D printer. Credit GNS Science.

Slab of rock from Golden Bay, showing many specimens and several different species of fossil graptolite. Graptolites were a type of colonial animal that lived floating in the ocean. In life, each “tooth” on a colony corresponded to a small cup that contained one animal, and the colonies housed many animals. These animals used tentacles to feed on particles of food in the water. Each colony has been flattened during the fossilisation process, so that now the colonies look like drawings on the rock. The graptolites were a major component of the oceanic ecosystem between about 500 and 400 million years ago, during the Paleozoic Era. Although they were a diverse and ‘successful’ group of organisms for about 80 million years, they became extinct 411 million years ago. The long dimension of the slab is 18 cm

Fossil turret shells from Hurupi Stream, southern Wairarapa. The snails are encased in rock and have been partially worn through, so you are looking at cross-sections of the shells. The species is called Zeacolpus taranakiensis and these animals lived on the sea floor about 10 million years ago, in a shallow sea that covered much of the lower North Island. Each snail is 1-2 cm long.

A different sort of fossil: this is a trace fossil – the marks left in sediment by the activities of an animal. In this case, some form of worm-like animal was burrowing within sea-floor sand, forming a set of radiating chambers that were subsequently infilled with different coloured sediment and preserved once the sand was turned to rock. These burrows are about 4 million years old and were observed on the coast of Hawkes Bay. Dinosaur footprints are another sort of trace fossil. Credit James Crampton

Bed of fossil molluscs (snails and clams and their kin) at White Rock River, Canterbury. The larger visible fossils are mostly the turret snail Tropicolpus abscisus, but there are many other species present also. These fossils are about 18 million years old. This shellbed illustrates a tiny part of New Zealand’s stunning fossil record of marine molluscs of the past 50 million years, which is the best in the Southern Hemisphere for this interval of time. The richness of this fossil record allows New Zealand paleontologists to tackle some fundamental questions about the nature of life on Earth and also the nature of the fossil record itself.

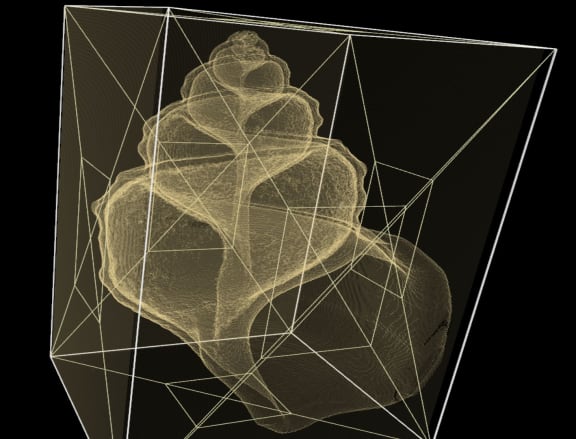

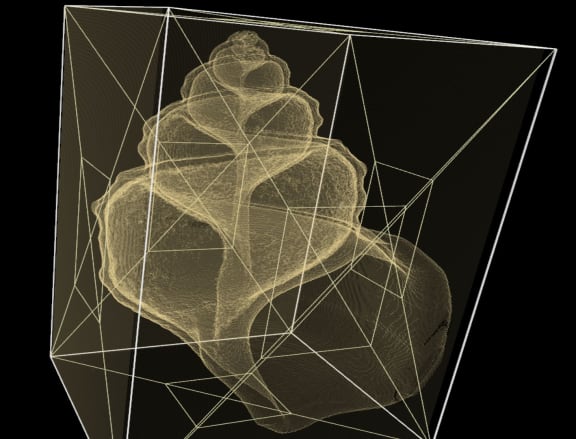

The future of paleontology? Snails are, today, one of the most biodiverse groups of organisms in the oceans. This is a 0.63 million-year-old fossil snail, Pelicaria vermis, that has been scanned in a high-tech scanner called a synchrotron and digitally removed from the rock, so that it can be studied inside and out and analysed mathematically. This work, by my former PhD student Katie Collins, aims to clarify just how, and how fast, snails evolve. Credit: Katie Collins, Chicago University

Life on earth has been around 4 billion years, but around 600 million years ago 'complex life' evolved, scientists generally believe.

It's still up for debate whether this evolution was inevitable or a chance coincidence, but we do know that we are living on and ourselves part of a 'microbe planet', Crampton says.

"What we see as life – the kauri trees and the people and the chimpanzees – is just this tiny little icing on the cake of life."

"99.9 percent of the life that's ever lived is extinct now."

Some say biodiversity has been increasing massively over millennia and others disagree, he says.

"So we said 'Let's look at snails and clams in New Zealand that we have this amazing database of and see what they show."

What they found was more or less constant diversity in the last 50 million years.

Layers of strata (sedimentary rock or soil) are like the pages of a diary with each layer preserving the fossils that were living at the time and the fossils are like the words on the page, Crampton says.

"It's an imperfect diary, but it's still remarkably good."

For some groups the fossil record is very good, for some it's not, he says.

"Your chances of being preserved as a dinosaur are very low, whereas your chances of being preserved as a mollusc are much higher."

Many believe there have been five big mass extinctions in the history of life on earth, but there's disagreement about where they were caused by.

Although it's commonly thought that an asteroid of estimated 10km-wide asteroid took out the dinosaurs, some scientists believe it was massive volcanic eruptions of a scale we can't imagine today which caused the extinctions.

Crampton thinks it was likely an unfortunate coincidence of the two.

"We know that there'd been huge eruptions going on in India, then oh dear, an asteroid came in, as well."

So what do we know about the dinosaurs that were once here?

Until 100 million years ago what we now know as New Zealand was just a little slice on the side of Gondwanaland – "a giant southern continent made up of Australia, and Antarctica, Africa and South America.

When we started drifting away 100 million years ago to become what we are today, there were some dinosaurs on this land, including long-necked sauropods, armoured Ankylosaurus and other two-legged carnivores.

So far the only confirmation we have of this is thanks to one or two bones found by amateur palaeontologist Joan Wiffen. Crampton says.